It sounds like the plot of a Twilight Zone episode, an Ursula K. Le Guin story, or the Pulitzer Prize winning 2002 novel Middlesex: There’s a place where, when girls hit puberty, they turn into boys.

Such a plot would prove rich territory - or a landmine - for anyone interested in how gender and sexuality develop. “Think of the scientific possibilities!” Slate wrote in 1997. “Finally, we could tease apart nature and nurture and see whether men and women differed because of how they were brought up as children.”

Yet, such a place - Salinas, a small village in the Dominican Republic - actually exists.

And though scientists have been aware of the genetic mutation that causes this curious condition for decades, the little-known, but extensively documented, story is the subject of a new BBC piece called “The Extraordinary Story of the Guevedoces”.

The translation of “guevedoce”: “penis at 12.”

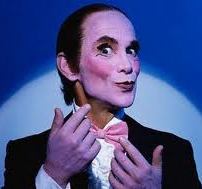

“I never liked to dress as a girl and when they bought me toys for girls I never bothered playing with them,” Johnny, formerly Felicita, told the BBC. “When I saw a group of boys I would stop to play ball with them.”

Johnny is not alone. As first observed by a Cornell University researcher in the 1970s, one in about 90 children in and around Salinas are affected by the mutation, which leads to low levels of an enzyme that typically spurs growth of the penis in utero.

In guevedoces, this growth is delayed until puberty.

And, after their transformation, many of the newly-minted boys prove heterosexual.

“So the boys, despite having an XY chromosome, appear female when they are born,” the BBC explained. “At puberty, like other boys, they get a second surge of testosterone. This time the body does respond and they sprout muscles, testes and a penis.”

Some guevedoces are tormented - called “nasty things, bad words”, as one told the BBC.

“When she turned five I noticed that whenever she saw one of her male friends she wanted to fight with him,” the mother of Carla – “on the brink of changing into Carlos” at 7, as the BBC put it - said.

“Her muscles and chest began growing. You could see she was going to be a boy.”

Though the case of the guevedoces, for some researchers, showed that nature is more important than nurture in directing sexuality, American pharmaceutical company Merck took the research to an unexpected place.

Guevedoces generally have small prostates. If the enzyme in question could be blocked by a drug, could prostate growth in adult men be inhibited?

Yes, Merck decided. The company developed the drug finasteride, more commonly known as Propecia, now used to treat male pattern baldness and benign prostate growth.

Some men reported the drug had strange effects on their sex drive.

“I’d be with a sexy woman, and there was just no interest at all on my part,” one patient said in 2011. “If anything, it was almost like I felt mild repulsion.”

But the guevedoces were not just of interest to Big Pharma. In a 1998 report, the Hastings Centre, devoted to ethical issues in medicine, discussed how the very concept of a third sex had changed the vocabulary and mindset of Salinas when it comes to gender.

“The sexually ambiguous child is born not into a world divided up into male and female, but into a world divided into male, female, and guevedoce,” the report read. “Different concepts, different facts of nature.”

“I love her however she is,” Carla’s mother told the BBC. “Girl or boy, it makes no difference.”